The Reformation is a hugely misunderstood and underestimated period of flux in Europe and beyond over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I have long been intrigued by the way religion not only underpinned society at every level during the Early Modern period, but how those influences are still relevant today. Having studied this period of history in depth at university I believe there are two significant themes of the English Reformation and its impact on liturgy and music:-

1) The Reformation was not an event which occurred at a single point in time.

The Reformation was not an event, it was more an evolutionary phase which spread out from Henry's break with Rome in 1530 like a mycelium which infiltrated every aspect of English life - and then re-wove itself through again and again creating a vast web of differing experiences, opinions and outcomes. It was the all and everything for the English people for almost 200 years, whether they participated religiously or not. In religious life it encompassed "English Catholics" with their highly latinised services, and Quakers who worshipped in words and silences only.Henry VIII lived and died a Catholic, his break with Rome was a matter of convenience only. Whilst the establishment of the Church of England was hugely significant nationally and internationally, the average parishioner would have noticed very little difference in daily worship during Henry's reign. For the common people, the dissolution of the monasteries would have had a far greater impact on their lives, since these institutions helped the poor and sick and were paid to sing masses for the souls of the dead. (i-see below)

|

| Henry VIII |

Music and Liturgy after the dissolution

Most parish churches had been endowed with chantries, each maintaining a stipended priest to say Mass for the souls of their donors, and these continued unaffected under Henry. In addition there remained over a hundred collegiate churches in England, whose endowments maintained regular choral worship through a body of canons, prebends or priests. All these survived the reign of Henry VIII largely intact, only to be dissolved under the Chantries Act 1547, by Henry's son Edward VI.

Edward, Mary and Elizabeth

After the death of Henry VIII in 1547, the new king Edward VI advanced the Reformation in England, introducing major changes to the liturgy of the Church of England. Thomas Cranmer had significantly greater freedom under Edward and in 1549, Cranmer's new Book of Common Prayer swept away the old Latin liturgy and replaced it with prayers in English. Church choirs began singing some songs in English, eg Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s. This brand new liturgy suddenly demanded that new music should be written for the church in English, and musicians of the Chapel Royal such as Thomas Tallis, John Sheppard, and Robert Parsons were called upon to demonstrate that the new Protestantism was no less splendid than the old Catholic religion. Some composers also began writing in a more chordal style because it was argued that the words were easier to hear and understand that way.

As archbishop, Cranmer put the English Bible in parish churches, issued the Book of Common Prayer, and composed a litany that remains in use today. His reform of the church in England strayed from the Lutheran model in its remodelling of the Daily Office. The first Book of Common Prayer of 1549 radically simplified the pre-Reformation canonical hours, of which seven had been said in churches and by clergy daily: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. Cranmer combined the first three services of the day into a single service called Mattins and the latter two into a single service called Evensong (which, before the Reformation, was the English name for Vespers). The rest were abolished. Cranmer was denounced by the Catholic queen Mary I for promoting Protestantism, he was convicted of heresy and burned at the stake.

During the reign of Mary Tudor (1553–1558), a revival of Catholic practice encouraged a return to Latin music, but after Elizabeth I ascended to the throne of England in 1558, vernacular English liturgy and music came back into favour. In 1559, Queen Elizabeth I of England issued a set of solemn Injunctions to strengthen the nation's Oath of Supremacy and its worship by the Book of Common Prayer. They specified that services should contain a hymn or song of praise to God, "in the best sort of music that may be conveniently devised." This phrase firmly ensconced choral music within the English church service and it helped establish the genre that would later be known as the anthem.

|

| Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury |

For composers at the time, this was a rollercoaster they had little choice but to ride. Thomas Tallis and William Byrd were particularly successful in this and navigated the twists and turns in religious music acceptability mostly with success. Both they and others like Orlando Gibbons bridged the gap from later Renaissance motets and madrigals to early Baroque music. The Word of God gained significant importance and liturgical music was intended to pass on a message, rather than ornament a Priest's spoken words. This period saw the birth of the verse anthem, a means of ensuring the Word of God was prominent through solo verses with more ostentatious polyphony between.

England under the Stuarts

James I continued in much the same vein as his cousin Elizabeth, although the Puritans were increasingly powerful. In an attempt to heal divisions and achieve conformity the Hampton Court Conference 1604 resulted in the Authorised King James Version of the Bible. (iv)

The English Civil War saw the victory of the Puritans, and under their rule during the Commonwealth music became almost completely absent, save for the singing of metrical psalms. Charles Etherington states it well when he says “The liturgy and the Prayer Book were abolished, choirs dispersed, all organs silenced, and many destroyed.” The need for simplicity for whole congregations that would now all sing psalms, unlike the trained choirs who had sung the many parts of polyphonic hymns, necessitated simplicity and most church compositions were confined to homophonic settings. (v)

Restoration England

At the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 enthusiasm for the older 'motet' style of anthem returned, but composers continued to write verse anthems, often on a grand scale - particularly for the Chapel Royal. Notable composers of verse anthems include William Byrd, Orlando Gibbons, Thomas Weelkes, Thomas Tomkins, John Bull and Pelham Humfrey. Although composing at the end of this period Adrian Batten was heavily influenced by it. To supplement his income while at Westminster Abbey Batten worked as a music copyist. The Abbey's account books record payments to Batten for copying works of Weelkes, Tallis and Tomkins. Batten is credited with the preservation of many pieces of church music of the time.

2) Audience Participation

The second theme is that of participation and purpose. The use of the English vernacular in services was revolutionary, and its impact cannot be overstated.Before the Reformation the vast majority of English people would attend church as instructed, most would understand very little of the service which was said and sung in Latin and obedience and compliance were automatic. After all, what they did not understand, they could not question. Once services were in English, the congregation were invited to participate fully - and therefore question. Without doubt this set in train the historical events of the next two hundred years. and became allied with the idea of social revolution, where knowledge is power. There was a fear amongst the elites that social unrest and change were inevitable (and undesirable) consequences of making the written word available to the masses. It is also true that many people (particularly in the north of England where the great landowners were staunch Catholics in the sixteenth century) feared change and clung to the familiarity and certainty of traditional Catholicism.

Martin Luther is the reformer credited with the start of the Protestant Reformation. Protestantism is associated with plainer worship, where the Word of God is paramount. Of all the reformers however, Luther had the most appreciation for music. Not only did Luther like and enjoy music, (he was a rather accomplished musician himself) he deliberately included music as part of the church service as a means for worship. He believed strongly in the ethical power of music and that through it one could glorify God and grow closer to Him. Music survived as an essential and integral part of Protestant worship as a means of glorifying God and connecting with him.

|

| "Luther hammers his 95 theses to the door" in Wittenberg, Germany |

John Calvin was less comfortable with music in religious services. He believed that individual prayer and worship was of extreme importance and that it far superseded that which happened on the outside. The idea that music should not hinder worship was essential for Calvin.

Calvin was also deeply concerned for the piety and religious devotion of parishioners, and considered that children could "teach adults simplicity, childlike devotion, and a sincere heart when singing, even though there might be problems with intonation and the like." He was responsible for adding children's choirs to worship music.

Hymns

Calvinists and radical reformers considered anything that was not directly authorised by the Bible to be a novel and Catholic introduction to worship and should be rejected. All hymns that were not direct quotations from the Bible fell into this category. Martin Luther however took the view that hymns were important for teaching tenets of faith to worshippers. He was the author of many hymns including "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" ("A Mighty Fortress Is Our God"), which is sung today even by Catholics.

The Reformation in England took this even further. Isaac Watts is credited as having written the first English hymn which was not a direct paraphrase of Scripture and has been called "the father of English hymnody". Charles Wesley's hymns spread Methodist theology, not only within Methodism, but in most Protestant churches. He developed a new focus: expressing one's personal feelings in the relationship with God as well as the simple worship seen in older hymns.

Antiphonal music

A special effect was attained by Andrea Gabrieli (1532 or 1533-1585) and his nephew, Giovanni (mid 1550s–1612): They placed different choirs in separate choir lofts on either side of the second level of the cathedral of San Marco in Venice to produce an impressive stereophonic effect, also called antiphonal.

Oratorios

Oratorios are similar to operas in structure, the main differences being that oratorios are usually on a sacred subject in contrast to the usually secular subject of operas, and that oratorios are rarely staged, whereas operas usually are. Many musicologists believe the word oratorio dates back to the time when Giacomo Carissimi (1605-1674) composed sacred music in a style very similar to the then new operatic style of Monteverdi, et al., for sacred concerts he directed at the Oratorio del Santissimo Crocifisso in Rome. Oratorios are typically composed to educate the public about stories in the Bible and disseminate the word of God whilst offering the composer a platform for complex composition rarely permitted within religious worship after the Reformation.

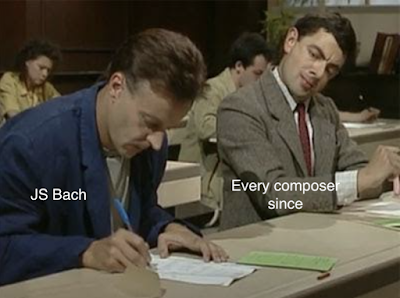

The Protestant Reformation had a profound impact on the musical world; it changed the way music was used in the church, how music was used in the reformers' respective countries and how it influenced later composers, particularly J.S. Bach, and therefore almost every composer since...

Like Luther, Bach strongly emphasised the importance of Scripture in his music and this could be clearly seen in his cantatas, which were meant to facilitate the truth of scripture through music rather than music as art for itself. His music is revered for its technical command, artistic beauty, and intellectual depth but also for being in many respects the culmination of a process begun in Wittenberg in 1517.

Bach was not widely recognised as a great composer in his lifetime, although his abilities as an organist were respected throughout Europe. Now generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time he is perhaps the fulfilment of the course of the Reformation, the fabulous end result which went on to be the inspiration for every composer since. As my fourteen year old sits composing Bach Chorales in his theory lessons, little does he realise the profound symbolism and legacy of this composer. The distillation of centuries of religious strife, the evolution of church music and liturgy over the Reformation in one man and his music, yet also the cradle of almost every composition since.

Additional Notes for those interested!

i)The dissolution of the monasteries in the late 1530s was one of the most revolutionary events in English history. There were nearly 900 religious houses in England, around 260 for monks, 300 for regular canons, 142 nunneries and 183 friaries; some 12,000 people in total, 4,000 monks, 3,000 canons, 3,000 friars and 2,000 nuns. The sudden cessation of their work with the poor and sick and masses for the souls of the dead created a great deal of fear and uncertainty. In the north of England this resulted in The Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536-7, the worst uprising of Henry VIII's reign. Not until the Elizabethan Poor Law Act of 1601 (which codified past laws) was limited progress made to reverse this social catastrophe. Whilst Cromwell is said to have wanted to help address poverty in Tudor England there was not the political will, and the safety net provided by the Monasteries had gone. (You can read more on this here.)

ii)"Defender of the Faith" is a title used by all kings and queens of England since the 16th century, despite the break with Rome. In her capacity as queen of the United Kingdom, Elizabeth II is styled "Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of Her other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith". The title "Defender of the Faith" reflects the Sovereign's position as the supreme governor of the Church of England, who is thus formally superior to the archbishop of Canterbury.

iii) Hymns cont. English hymn writers before Watts tended to paraphrase biblical texts, particularly Psalms, but Watts is credited as having written the first English hymn which was not a direct paraphrase of Scripture. Watts is said to have complained at age 16 that when allowed only psalms to sing, the faithful could not even sing about their Lord, Christ Jesus. His father invited him to see what he could do about it; the result was Watts' first hymn, "Behold the glories of the Lamb".

Later writers took even more freedom, some even including allegory and metaphor in their texts. Charles Wesley's hymns spread Methodist theology, not only within Methodism, but in most Protestant churches. He developed a new focus: expressing one's personal feelings in the relationship with God as well as the simple worship seen in older hymns.

iv) Music and liturgy under the Stuarts cont. James I tolerated English Catholics who took the Oath of Allegiance but the Puritans had the upper hand in the Church. Although strict in enforcing Anglican conformity at first as his reign progressed he largely gave up. In an attempt to heal divisions and achieve conformity the Hampton Court Conference 1604 resulted in the Authorised King James Version of the Bible.

v)Polyphony There is some evidence that polyphony survived and it was incorporated into editions of the psalter from 1625, but usually with the congregation singing the melody and trained singers the contra-tenor, treble and bass parts.

A very nice article which I enjoyed reading . My only disagreement is with the view that the Roman Catholic Church was a good church in England prior to break with Rome. There is ample evidence that it was a very corrupt and cruel church as a whole and that the Reformation progressively introduced the Church of England which was purer. The tragedy was that the desire by some educated people to rid themselves of everything Popeish,led to the destruction of much beautiful art and architecture.

ReplyDelete